- Home

- LaVoy Finicum

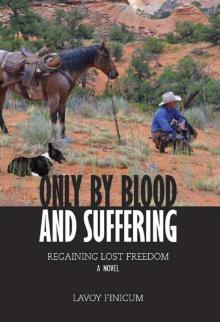

Only by Blood and Suffering: Regaining Lost Freedom Page 8

Only by Blood and Suffering: Regaining Lost Freedom Read online

Page 8

“In the process, government grows ever bigger and the resentment grows between the helper and the helped, because government is in the middle. There was a time in this country when a man would give freely of his time and means to help his neighbor without the government,” he concluded.

A river rat and a cowboy—he and Dad could live peacefully in the same community with no problems. Live and let live. Or, as the boatman quoted Thomas Jefferson, “If it neither breaks my leg nor picks my pocket,” what is it to me?”3

That night we made camp on another beach, and by noon the next day, we were beached at Tapeats River canyon. Thunder River flowed into Tapeats only a quarter a mile up the side canyon. My spirits were lifting. Home was within reach. All the worst of the challenges were behind me.

I thanked the lanky boatman and the young couple again. Taking the two 9-mil pistols which I had taken from the rangers, I handed one to the boatman and one to the young man. The way the young man handled the gun, I was sure he had never fired one. As the boatman stuffed his 9-mil into the back of his pants, I could tell he was at home with it. Both of them grasped the immeasurable value that the guns now represented.

“Don’t worry about them,” the boatman said nodding to the young couple. “I’ll show them how to shoot it.”

As the boaters had lunch, we unloaded our bikes and packs. I gratefully accepted food that my new friend, the boatman, offered us. Along with what remained in our packs, it was enough to get us home.

As we parted, the tall man took me by the hand and said, “I hope to see you soon.”

By the time the river boats were back in the main current, Jill and I were well up the trail to Thunder River. It was not far and soon we could see the river breaking free of the mountain, a river born fully mature. It came out of a cave not far up the canyon wall. Cascading over the boulders below, it was a pretty sight. I remembered riding our horses down here and camping with Dad as a small child. Horses had long been banned from this place, but those were good memories.

We pushed our bikes up the steep trail coming out to the Esplanade bench. We were still low enough in elevation that it was a light rain that was falling on us and not snow. The long trail on the bench was not hard going but it was growing dark and baby Jamie was taking a turn for the worse.

Turning off the trail I found a small overhang that sheltered us from the rain. I quickly built a small fire to help warm my family. While Jill tried to comfort the struggling baby, I hunted for more firewood. Wood was not plentiful on the bench but I found a dead cedar tree that would give us fire through the night.

By the time I had broken enough branches and hauled them to the overhang it was fully dark. With the fire to our front, the wall to our backs and the overhang above us, it was not uncomfortable. The warmth of the fire was reflected off the red sandstone rock and there was no breeze.

I did not like the worried look on Jill’s face and there was a knot forming in the pit of my stomach.

“She won’t nurse, Dan, and it feels like her fever is spiking.”

I felt helpless. With a piece of cloth torn from her shirt and wetted with water, Jill was wiping the baby’s burning brow.

“She is struggling to breathe and I’m worried.” Jill said.

I knelt beside them and felt Jamie’s forehead. It was very hot. I poured more cool water on the rag for Jill. From the pack I found some aspirin and crushed it on a flat rock. Giving the powder to Jill, she put some in the baby’s mouth. By the fire light, it looked like Jamie was able to swallow it. I hoped it would bring the fever down.

As the night hours crept by, the light rain continued to fall. I kept the fire going as Jill tended our little one. The baby’s breathing was very labored and shallow. Her fever had come down only slightly.

Another hour went by and the baby’s battle for life became more desperate. The little body was tiring from the struggle and her breaths became more shallow and rapid. It was more than I could bear to watch and I stepped out into the dark. I had been taught that there was a God and prayer was part of my up-bringing.

Finding my way through the dark, I came to a large boulder. There I knelt down and prayed, something I had not done in a long time. I felt no relief. Standing up I could see the small overhang. The light from the fire danced upon the rocks. I could see Jill kneeling next to the fire no longer holding our baby. Before her knees, lay the little child wrapped in my coat.

I stood there in the dark as the quiet rain fell upon me. The knot inside of me swelled as if it would burst. I did not want to return to the fire but my feet carried me back. I reached the edge of the firelight and Jill looked up. In the soft light of the fire, her cheeks were glistening from the tears that ran down her face.

It was more than I could stand. I turned my back and stepped away from the light. I made no sound as my heart was wrenched and the tears came. I had failed them. I had let them down.

Anger rose up inside of me. I wanted to blame someone, anyone. But who? Who had allowed our country to become so vulnerable?

Dad had said that when this country got hit it would be a surprise to all but the real power brokers. I had a hard time believing his conspiracy theories but not anymore. Was I not standing in the dark rain, on a bench in the Grand Canyon? Was not my wife and two year old boy huddled together by the body of my dead baby? It was no theory now! It was real and the cost was dear.

My fist clenched as my anger turned from anger to hate. Would to God that the traitors could be tried by a jury of their peers. I would gladly tie the noose and see them hung by the neck till dead.

I do not know how long I stood there as I slowly descended into a bitter pool of hate. Then I felt a touch upon my arm, a soft touch, one that I loved. Jill stood before me. Taking both of my arms, she pulled me close to her face.

“Dan, you can’t blame yourself.”

But I did. I blamed myself and anyone else I could think of.

“I do. I do blame myself. I should have left days earlier. We would be safe at the ranch by now and Jamie would not be dead.”

“We made that decision of when to leave, together. I don’t blame you, Dan.”

I was amazed at Jill’s inner strength. A mother who had just lost her baby and here she was trying to comfort me.

“Dan we still need you. Little Will and I still need you. We have lost Jamie but we are still a family and we can’t make it without you.”

She was pulling me back from the dark abyss.

“There is one thing that I ask of you. I do not want to bury my little girl in this lonely place. I want her body to rest in the Bonham cemetery and, when I die, I want my bones to rest next to hers. Promise me that Dan.”

“I promise, Jill. I promise.” The hate and bitterness melted away and allowed the “healing sorrow” to return.

Taking Jill in my arms, I pulled her tight. For a moment the rain stopped. The darkness around us lightened. Looking up, I could see a few stars giving their light to this sad place. I watched the stars for a minute, then they were gone as the gentle rain resumed.

_____________________

1. The FDA has been on a rampage against raw milk seeking to pass the “Leahy Bill” that makes it possible to sentence raw milk producers up to ten years in prison.

2. MuniLand-Reuters; cost of the war on drugs is more than 50 billion a year.

3. Thomas Jefferson quote, “It does me no injury for my neighbor to say there are twenty gods or no God. It neither picks my pocket nor breaks my leg” (Thomas Jefferson, Notes on Virginia, 1782). This quote was in defense of the people’s right to live their life without interference from the government or their neighbor.

Chapter 12

CAT

February 12th

It took me five days to get past Grants, New Mexico. Packing a baby in front and a pack on my back, I was struggling. I had made a sling that went over my head and one shoulder from bed sheets to cradle the baby in. It helped, still, my muscles ached and my should

ers were sore from the pack’s straps. It had not snowed hard but the snow seldom stopped and it was starting to pile up.

Grants had not been a pretty sight. Refugees from the freeway had fled into the town. Desperate and hungry, people started taking what they could to stay alive. From the hills above the town, I watched small bands of men gather in the streets. There were small neighborhoods that had tried to protect themselves by blockading their streets. I watched as these bands fought the fortified districts and each other.

Hunger was the propellant. It had been only five days and the town was acting medieval. Those that came off the freeway came with no food. My guess was that half the town’s residents had kept less than five days of food on hand. In the five days that it had taken me to get from Albuquerque to Grants, a simple American town was coming apart at the seams. It was dawning upon them that there would be no trucks making food deliveries to the stores anytime soon.

I left Grants and traveled on. It took me extra time and effort to avoid the small bands of people that were leaving the towns to scavenge. I headed northwest in the direction of Canyon De Chelly. Dad had chosen the back roads that had the least amount of population for the route on which to place the stashes. I was grateful for that and trusted no one that I saw.

“You have to count on yourself, daughter.” Dad would say. “When things are in a bad way there are few people who will be willing to help you. Most won’t be able to help themselves. In days like that, trust will be the rarest of commodities.”

* * *

It was now seven days since I had passed Grants. I was cutting across the Navajo Indian Reservation. Things were starting to stack up against me—the snow, the sore muscles, the weight of the baby, the pack and the gun. The top of my shoulders were tender and very sore from the straps of the pack and the sling of my rifle. But it was the snow that was troubling me the most. I had never seen a storm that would not go away. Eleven days there had been of grey clouds. Grey clouds that snowed, never hard, but endlessly. Slowly the snow was stacking up and was now over ten inches deep.

Day after day, the travel through the snow was becoming more difficult. Half of each day was spent trying to gain some ground towards home. The second half of the day was spent trying to find firewood close to some sort of shelter. “Some sort of shelter” too often meant, under a cedar tree. The last time I had truly been warm was the night I slept on the floor of the home where the baby’s mother had died, the home where I shot those men.

I found it strange that I seldom thought of the men I had recently killed. I neither thought about them nor felt remorse for shooting them. I had hunted most my life with Dad. I had more tender feelings for the coyotes I shot than I did for those men. A coyote does by nature what a coyote does. He is an opportunist. If he can get a new born calf he will. That’s his nature, animalistic. He preys upon anything that is weaker and only fears that which is stronger.

Those men were like coyotes, only worse. A coyote doesn’t have a choice to be predatory or not, it is his nature. But, those men had a choice. They had a choice to show compassion or to be predators. They had chosen to be lower than a coyote and it was only strength that stopped them. They had met their “day of reckoning” when I shot them. Now the Judge of the quick and the dead would weigh the intents of their hearts.

Setting the butt of the rifle in the snow, I leaned upon the muzzle. It was no more than midday and I was tired. I was tired and I was hungry. It had taken me four days between the last two stashes. That had left me a day short on food. Packing the extra weight of the baby with the cold and snow I was burning a good deal more calories that I was taking in. It left me weak.

I should have found the next stash yesterday but I could not find it. The snow and low clouds were making it extremely difficult to locate the landmarks. I was getting worried.

Straightening back up, I pulled open the front of my coat a little. A smiling face of a baby looked up at me and a tiny hand reached for my cheek. Vondell was not worried. She was thriving. Bundled next to my body, she was warm. When I walked it was calming to her and I could often hear her making the cooing sounds of a contented baby.

The only food left in my pack was the cans of powdered baby formula. I would not even let myself consider the thought of using them for anything but the baby.

My legs were shaking from the exertion I had made this morning walking in circles looking for the stash. It was the lack of food that made me tremble.

I knelt down in the snow and laid my head against the rifle that I was leaning upon. My black hair lay in wet strings against my cold cheeks. I was on a ridge and a wide draw lay below me. In the draw was a rusty windmill that was pumping water. The water ran into a ring tank that overflowed to a dirt reservoir. I did not remember this windmill at all. The food stash was lost to me.

“Oh, Dad, I wish you were here,” I thought in my heart. It was getting hard to keep up good courage.

As I knelt there, resting in the snow, I watched the blades of the windmill turning, pumping the water. As I watched, the breeze picked up and the blades began to turn more quickly. Then, for the first time in the last eleven days, it really started to snow. The flakes were big and they were coming fast. The visibility was starting to diminish and the windmill was harder to see.

Then I saw it. Something was moving on the opposite ridge of the draw. At first it was just a dark spot in the falling snow. It was moving slowly down to the ring tank. I slipped off my pack and coat. Then I pulled the baby from her sling, wrapped her in the coat and laid her next to the pack. In a low kneeling position with one knee down and one knee up, I racked back the bolt action of the rifle. The bullet, with its shiny brass case, made a metallic sound as I slid the bolt forward and charged the gun. I steadied the rifle in my arms. With my elbow resting on my knee, I tucked the butt of the Remington snugly against my shoulder.

Through the scope I could make out what was coming. It was a brindle colored bull. Large and heavily horned, in his prime and looking to weigh over 1700 pounds. It was a beautiful animal and the heavy muscles rippled under his winter coat.

Excitement came upon me as I watched the animal through the rifle’s scope. I had hunted deer with Dad and several times, after making a kill, we had roasted fresh venison over a fire before dragging the deer back to the truck. That bull was like ten deer and it was food. My mouth started to water and visions of a juicy steak roasting over a fire came to me. I could hear it sizzling over the flames, I could smell it, I could taste it.

I placed the cross-hairs just behind the front shoulder and low in the chest of the bull. My finger started to take the slack out of the trigger. This was an easy shot, no more than 50 yards but, my finger froze upon the trigger as a voice came into my head.

“Cat,” it seemed to say. It was the voice of my father. “Cat, if it’s not yours, leave it alone.”

But I needed it, I needed food. If I did not get food I would not live and if I did not live, neither would the baby. Surely, I was justified in taking this animal for the baby.

“Your needs do not grant you rights. You have no right to take what belongs to another man,” I could hear him say.

“What about the baby?” I thought. I had grown up watching our government take from the producing segment of our society to help the children. If they could do it, why not I? This was a matter of life and death.

Dad seemed to rejoin my thoughts, “If you take without permission, even to give to those who are in need, it is still robbery. The same holds true for government. When they take from one group and give to another it is plunder, plain and simple. We cannot do it individually, and since our government derives its powers from us, they have no right to do it either.”

My imaginary argument with Dad had just turned political.

“Damn,” I cursed to myself.

I lowered my rifle. Someone else owned that bull. Maybe that person was comfortable and well fed or maybe this animal was critical for his survival; to the s

urvival of his family. I could not do it. I could not shoot the bull.

My conscience was at rest but my hunger pangs were not. The storm was increasing in intensity and food now became secondary to shelter and heat. I wiped the snow that was collecting on the baby and cradled her back in the sling. With the coat and pack on, I picked up the rifle and moved forward. I walked down to the windmill to fill my water bottle. The baby would need to be fed again soon.

As I approached the ring tank the bull’s head came up with water dripping from its mouth. With head high, he watched me for a moment. He was a wild animal and had a powerful set of sharp horns. He dipped his head and tossed his horns, challenging my approach. He was king of this domain and I was an intruder.

Loaded as I was, I was in no condition to run, so I clicked off the safety of my rifle and fired a shot into the air. With a snort, the bull turned tail and bolted for the cedars. He was soon lost from my sight in the big flakes of falling snow.

I filled my water bottle and checked my compass.

“Move forward, always move forward,” I could hear my father’s voice again in my weary mind.

I walked in the direction of home. A home that now felt to be years away from here. The distances between my pauses for rest became shorter and I was laboring in my breathing.

One hour passed, then another. I could find nothing but low scattered cedar trees that offered almost no shelter. Wood. I need wood for a fire. I was giving up on shelter and desperately looked for wood to burn. The cedar trees were small, green and wet. I could not find a dead one or even one with dead branches. If I could not get a fire going the baby and I would not make it through the night.

I stumbled and fell forward into the snow. The rifle disappeared in the deep snow as I stretched out my hands to catch myself. I was very cold now and it was getting dark. I struggled to my feet and felt in the snow for my rifle. Too exhausted to wipe the snow from the gun, I slung it back over my sore shoulder.

Only by Blood and Suffering: Regaining Lost Freedom

Only by Blood and Suffering: Regaining Lost Freedom